The greatest risk when feeding a patient with swallowing problems is food entering the airways.

Penetration is defined as the passage of the bolus into the airways above the vocal cords. Normally, this penetration is resolved by the protective cough reflex.

Aspiration is defined as the passage of food residues under the vocal cords. In this case, the cough reflex is not sufficient to expel these residues, with serious consequences for the respiratory system.

Aspiration pneumonia is the most common cause of death in patients with dysphagia due to neurological disorders. Aspiration is defined as the inhalation of oropharyngeal or gastric contents into the larynx and lower respiratory tract. The risk of aspiration is relatively higher in elderly individuals due to the higher incidence of dysphagia and gastroesophageal reflux. After aspiration, various pulmonary syndromes may occur depending on the amount and nature of the aspirated material, the frequency of aspiration, and the host's response to the material itself.

Aspiration pneumonia proper – or Mendelson's syndrome – is a chemical injury caused by the inhalation of sterile gastric contents, while ab ingestis pneumonia is an infectious process caused by the inhalation of oropharyngeal secretions colonized by pathogenic bacteria; although there is some overlap between them, they represent two distinct clinical entities.

Aspiration pneumonia is characterized by chemical burns to the tracheobronchial tree and lung parenchyma due to the acidity of gastric contents, followed by an intense parenchymal inflammatory reaction. Since gastric acidity prevents the growth of microorganisms, microbial infection plays no role in the early stages of aspiration pneumonia, but may play a role at a later stage, although the incidence of this complication is poorly understood. However, it should be remembered that when the pH of the stomach increases following the use of antacids or proton pump inhibitors, which are frequently used in the elderly, potentially pathogenic microorganisms may colonize the gastric contents.

The signs and symptoms of patients who have aspirated gastric contents range from gastric regurgitation in the oropharynx to the onset of rales, cough, cyanosis, pulmonary edema, hypotension, and hypoxemia with rapid progression to acute respiratory distress and death. In most cases, there is only shortness of breath or coughing, while some patients experience what is commonly referred to as silent aspiration, which can only be detected radiologically.

Aspiration pneumonia develops as a result of the aspiration of secretions colonized by microorganisms from the oropharynx; however, it should be noted that this is one of the main mechanisms through which bacteria—such as Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae, which colonize the oropharynx—penetrate the airways. In fact, about half of healthy adults aspirate small amounts of oropharyngeal secretions during sleep, but their microbial content is continuously eliminated through active ciliary transport, normal immune mechanisms, and coughing. However, if these mechanisms are compromised or if the amount of aspirated material is abundant, pneumonia may occur.

In elderly patients and those who have suffered a stroke and are affected by dysphagia, there is a strong correlation between the volume of aspirate and the development of pneumonia.

The diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia is based on radiographic evidence of pulmonary infiltrates in the bronchopulmonary area. Factors that increase the risk of oropharyngeal colonization by potentially pathogenic microorganisms and that increase the bacterial load may increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia; for example, this risk is lower in edentulous patients and in elderly patients who receive effective and thorough oral care. In fact, inadequate oral hygiene can lead to abundant oropharyngeal colonization by potential respiratory tract pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus in community-acquired pneumonia in elderly individuals.

With regard to the microbial agents causing aspiration pneumonia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Gram-negative bacteria were found to predominate in patients with aspiration syndrome contracted in hospitals, while Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Enterobacteriaceae are prevalent in community-acquired pneumonia.

It is clear that food passing into the respiratory tract occurs more frequently during meal administration in dysphagic patients, even in the early stages. When this passage manifests itself with a feeling of suffocation, persistent coughing, and the appearance of a red or cyanotic complexion, the phenomenon becomes extremely evident to those administering the food.

It can be much more dangerous not to address signs of small amounts of food passing into the bronchi—silent aspiration—as this often goes unnoticed by the patient. Certain phenomena should raise suspicion, including:

- Constant occurrence of involuntary coughing immediately after, or within 2-3 minutes of swallowing a bite

- Appearance of hoarseness or huskiness in the voice after swallowing a bite

- Leakage of liquid or food from the nose

- Presence of fever, even if not high – 37.5-38°C – without obvious causes; fever can in fact be a sign of inflammation or irritation due to food passing into the airways.

If even one of these signs is detected, it is advisable to report it immediately to your doctor and/or to the person who is primarily responsible for treating your dysphagia.

It is worth noting that the passage of food into the respiratory system, through the trachea into the bronchi and then into the lungs, even in small quantities but with repeated episodes over time, can lead to a form of pneumonia that begins as inflammation but can develop into a more serious infection, especially if food continues to enter the bronchi. Therefore, great care is required when administering meals, both in terms of how they are administered—posture, timing, etc.—and in terms of food choices.

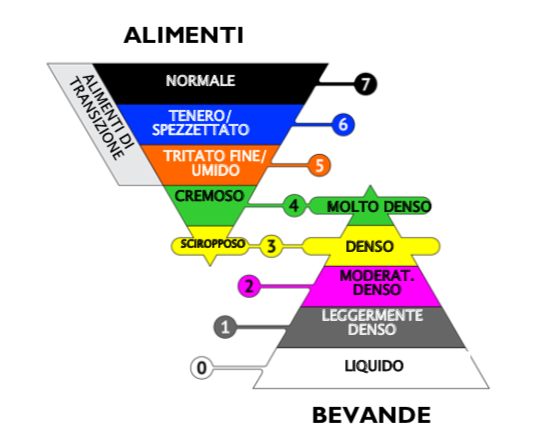

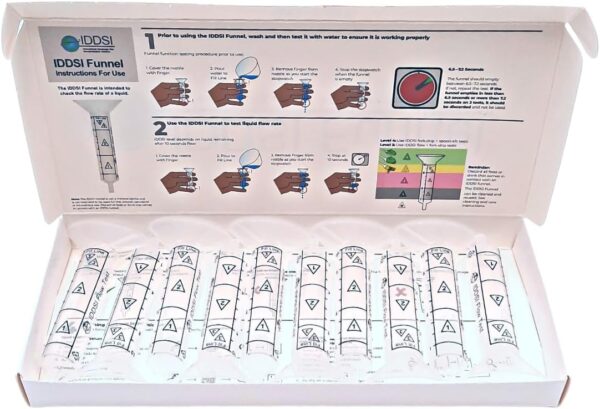

When feeding patients with swallowing difficulties, it is necessary to plan a progression of foods based on the patient's swallowing ability. The choice of foods, which depends on the type and degree of dysphagia, should be guided primarily by the following criteria:

- Patient safety by limiting the risk of aspiration—food entering the airways—through the selection of foods with suitable physical properties (homogeneity, viscosity, cohesion)

- The patient's nutritional requirements, with particular reference to protein, calorie, and water intake, any dietary requirements, and food preferences.

While it is necessary for food to be varied, appetizing, and nutritionally adequate, it is also a priority to implement all measures aimed at preventing the risk of food entering the airways and the consequent risk of aspiration pneumonia.

Among these actions, we recommend paying attention to posture, applying correct administration methods, and dividing the daily food intake into several meals (at least 5) in order to reduce the patient's effort.

However, we strongly recommend that food choices be made with great care and that their rheological parameters (in particular, homogeneity, absence of double phase, consistency, viscosity, viscoelasticity, and cohesion) be suitable for dysphagic patients, remaining absolutely constant in various contexts of use, from preparation to administration.